Narrative in street photography: revealing a paradox

By its own spontaneous and candid nature, street photography doesn’t often lend itself to the creation of intentional narratives. Why? Because narratives assume that several photographs make sense together to tell a particular story, evoke particular feelings, build upon common themes. But if each shot is an unique as our vision of the world in this moment, can narratives ever exist in street photography? Can the lack of planning and premeditation be somewhat overcome to create a piece of work that tells something bigger than each shot on its own?

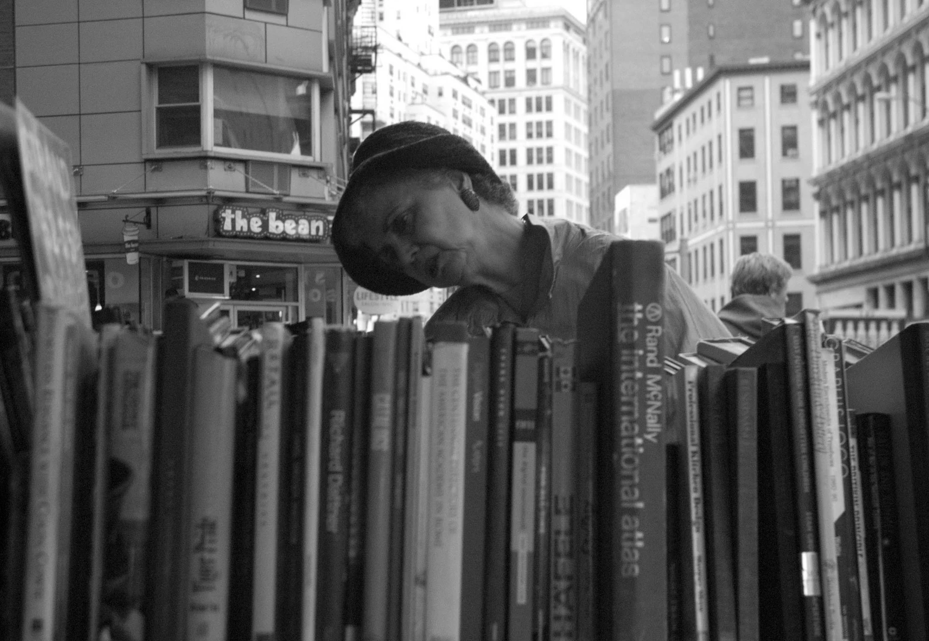

Rohit Vohra shares: “I rarely take photographs with a series in mind. Sometimes a strong photograph will lead to an idea and that idea will stay in the subconscious mind, patterns emerge and you soon know there is a potential of a series. Most of my series have started with a few existing photographs or at least one strong photograph, but I have never consciously looked for the next shot. It’s only while I am taking a shot, or a little after it that I might feel it fits well in an existing series.”

Image by Rohit Vohra

The role of narratives in sharing with the world

Yet, most often than not, published artists and photographers have been able to present their work with a specific angle and narrative, a way to create sense out of an accumulation of images, whether in the context of an exhibition, a publication in a magazine, or the creation of a photobook. Photographers, this is a fact, do not randomly display their images. They think through them carefully, and organize them in ways that create meaning and communicate something unique about their work.

Melissa Breyer shares: “To get published, it’s important to think through narratives and series. Telling the specifics of one’s work is an essential factor in getting seen.” While she considers most of her work to be an ongoing series, she now enjoys smaller bodies of work. From a street perspective, she’s quite content with where she is. Yet she’s always hoping that there will be something new, a small change that will keep her curious and interested in street photography. Some idea that will flourish and become a whole narrative on their own.

Image by Melissa Breyer

Narratives can be told at portfolio-level, expressing the intent behind an entire body of work, or may be expressed through smaller bodies of work: a defined set of images working together as a series or the output from a project for example.

On the creation of a portfolio

Building a portfolio requires to select images that provide a consistent view of the work. For a portfolio to be remembered, there must be strong unicity in the work being showcased, unicity in places, time, styles, moods or subjects / situations.

Martin U. Waltz has the ambition to move beyond single images to create a narrative more specific to his work – with consistency in places, subjects, location. This is why on his website, he removed all photos not taken in Berlin. Indeed, after showcasing images from all locations for a while, he realized that his travel photographs could never really expressed the same raw feeling that he tries to convey through his work. But Martin doesn’t stop there: he continuously pays attention to the recurrent elements in his photography to refine his style and unique vision – e.g., repetition in moods and situations, and eventually create a “unique narrative between myself and my work”.

Image by Martin U. Waltz

In photography, Mike Lee believes that you need a style or narrative to go with your own work. Photographers need to define what street photography means to them if they ever wish to create interesting work and get published. A few years ago, Mike published Invisible Mirrors with Corridor Elephant editions. Packaging his images into a narrative was an integral part of the editing process. He asked himself what his best pieces were, then what narrative or thread was connecting each of these images. For him, unicity in his work is more easily achieved because of the short window of time and place that he allows himself to shoot: 8-10am on his way to work. Once Mike had to choose 200 pictures based on his PhotoVogue portfolio – curated by a PhotoVogue editor: “Whether we agree with the curator or not, an external eye can make us see patterns in our work that we wouldn’t have seen otherwise. This helped me improve my editing skills to be published / accepted.”

Image by Mike Lee

Intentional series in street photography

CASE STUDY: MELISSA BREYER

Steam Systems

“I think of my whole body of work as one on-going series. Part of that is because I don’t have the chance to photograph outside of NYC very often which defines a theme already, but also because I have narrowed down my style to a pretty streamlined version of what I want to document and express. Within that, more specific themes may emerge as a series. I am definitely drawn to certain themes, and if I find myself collecting a number of photos that I like that share commonalities – and I feel that they have stories to tell as a collection – then I start looking for more with the idea of grouping them together.”

Image by Melissa Breyer

CASE STUDY: MARTIN U. WALTZ

New Year’s Eve, Backstage

“Themes are preferred subjects, stuff I just care about, lenses through which I see the world. They are created at posteriori through looking at patterns across my work. Unlike themes, my series are quite intentional, but are not always thought conceptually. They are built on unicity in places and moods, and are more documentary than the rest of my work. Eventually, I am inspired by the flow, by the moment. Series will always be an evolving dialogue created from the raw material, not the other way around.”

Image by Martin U. Waltz

Conclusion

- Narratives are what connect images across our work: a way to provide meaning beyond any single image, and to be remembered among many photographers and artists

- Street photography, by its candid and spontaneous nature, makes it harder to articulate intentional narratives – yet published authors have not chosen their images randomly.

- We can tell narratives in various ways: broadly, through showcasing a portfolio, or through narrow bodies of work – either themes, series or projects

- Unicity in places, time, situations, moods or subject matters provide the foundation for presenting images in a meaningful way.

- Eventually, to prevent against becoming formulaic, many street photographers create series organically, through a combination of intention and improvisation.

Image by Nima Taradji